As you read through your Old Testament, you will come across a rather curious genealogy at the beginning of 1 Samuel. We are well familiar with Samuel as God’s prophet and pupil of Eli the high priest. 1 Samuel opens by tracing a man named “Zuph the Ephraimite.” It appears difficult to explain that an Ephraimite could have such place in the Tabernacle service. There are several elements to this discussion. When pieced together, I believe it shows an excellent literary commentary on that period of time, a masterful display of God’s providence and mercy, and a subtle but powerful anticipation of the Messiah himself.

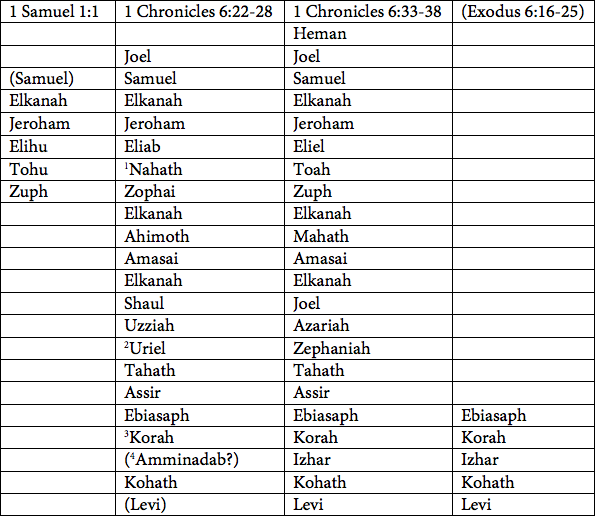

Compare the lists:

We must first notice the records of Samuel’s forefathers. There are three accounts of Samuel’s line. Let’s see them compared:

1- The name Nahath is admittedly different from either Tohu or Toah, but shares similar Hebrew characters in reverse.

2- Uriel and Zephaniah are quite different. I do not see any spelling variances. It’s just a different name. Perhaps still the same person.

3- Exodus 6 sheds light on understanding successive verses concurrent generations. We learn that Assir and Elkanah were most likely concurrent children of Korah, and the line of 1 Chron 6:33-38 agrees and traces the lineage through Ebiasaph directly back to Korah.

4- Amminadab is the name of Aaron’s father-in-law recorded in Exodus 6:23. It’s a different branch of the family, so I am less inclined to think it is a text corruption. It is more likely that Amminadab is another name for Izhar or was another name for Amram (Amram is a different branch of the family, but still a son of Kohath).

Surely, several of these lines have room for explanation in other settings. The focus, here, is upon the latter stages of the genealogies. Although there are several spelling changes (and some rather hard to explain alternative names) these three lines agree on the latter stages. There is a certain level of ambiguity in the Hebrew genealogies where generations are skipped, whether a list of children should be in the same generation of successive generations, and whether name repeats are back-tracking or unique individuals. We are actually lucky, in this case, to have three different tellings (four if we go back to Exodus 6) by which to compare these details. Our focus is going to be on 1 Samuel 1:1.

A note on the words:

You may notice some translation variances. Some translations (KJV, ESV) use the term “Zuph an Ephrathite” while others (NASB, NIV) say “Zuph an Ephraimite.” It comes down to interpretation. Some passages are rather clear that the word “Ephrati” should intend the tribe of Ephraim (Judges 12:5; 1 Kings 11:26). Other times it is used to describe those from Ephrathah (Bethlehem) (1 Samuel 17:12; Ruth 1:2). The confusion stems from the name “Ephrath” who was a prominent wife of Caleb son of Hezron. 2 Chronicles 2:24 even combines Caleb-Ephrathah as the name of a location in which Hezron died. Later on (vs 50-51; and 4:4) we discover that Bethlehem was a grandson of Ephrathah. Thus, the Israelites sometimes referred to Bethlehem as Ephrathah (Genesis 35:19; Ruth 4:11; Micah 5:2). To be called an Ephrathite identifies one with the region of Bethlehem, not from the bloodline of Ephrathah. In the case of Ruth, her family was from Bethlehem (1:22), thus Elimelech’s family were called Ephrathites (1:2). Jesse is called a “Bethlehemite” in 1 Samuel 16:1, which is synonymous with “Ephrathite of Bethlehem” in 17:12.

The two designations of “Ephrathite” are linguistic coincidence rather than family association. Even though Hebrew “Ephrati” looks identical, they are two different words because they stem from two different linguistic sources. All other references to Ephraimites bear the contruction “of Ephraim.” Context must tell us whether “Ephrati” denotes the region of Ephrathah or the region of Ephraim. In the case of Ruth and Jesse, the passages are overtly clear about their ties to Bethlehem. In the case here in 1 Samuel 1:1, I believe the text is equally clear that Ephraim is in mind. Therefore, I believe the translation “Ephrathite” in this verse to be incorrect, and “Ephraimite” to be accurate.

Although the following does not change our interpretation, I also want to quickly point out the phrase “man from Ramathaim-zophim” (NASB) to be confusing. Elkanah is from the city of Ramah, and the area is associated with Zuph. Therefore I believe the NIV to have the best understanding with “man from Ramathaim, a Zuphite from the hill country of Ephraim.” I believe this properly identifies Zuph as coming from the hill-country of Ephraim, rather than implying that Ramah was in the hill country of Ephraim (it is not, and is clearly established as being Benjamite territory). Therefore Elkanah himself was born and raised in Ramah, and was not himself from the hill country. The designations to Ephraim are redundant to distinguish the Zuphite family from the native Benjamites (we will explore this more later).

Literary explanations:

Every genealogy is given for a reason. Each of these genealogies accomplish a different nuance to the purpose of the authors. You may readily notice that some genealogies trace downwards toward a certain son. Other genealogies trace upwards towards a certain ancestor. Most genealogists perceive the downward genealogies as tracing qualities or characteristics. The forefather is passing on something to his children. The upward genealogies are perceived to trace pedigree or authority. The child inherits a title or serves in a role which has authority based on the ancestor. Applying this to our three lists gives one kind of explanation. 1 Chronicles 6:33ff is tracing from Heman upwards. Heman is the patriarch for a very important Levitical family whom God authorizes to prophecy in song and instrumentation at the temple. Heman’s pedigree here affirms his authority as a prominent Levite and Prophet. 1 Chronicles 6:22ff is passing on the leadership baton of Kohath’s family. The sub-tribe of the Kohathites were charged with taking care of the ark, the holy place furniture, the service utensils, and the Holy of Holies veil (Numbers 3:27-32) This gives Samuel direct right to serve in the tabernacle and care for the logistics of service.

The head-scratcher is 1 Samuel 1:1. Why, if Samuel was about to be introduced as dedicated to the house of God, would he be given a pedigree from Ephraim? The literary explanation regards the phrase “from the hill country of Ephraim.” Since the reader has just finished the awful stories of the Judges, this phrase should be familiar (used over a dozen times). Close at hand, Judges 17 attaches this phrase to Micah and his hired Levite (Judges 17:1, 8). The hill country of Ephraim is where the Danites passed through and robbed Micah (18:2, 13). This story describes blatant violations of the tribal duties, violations of the priesthood, and violations of the worship process. At the end of that story (18:31), the house of God was at Shiloh (where they were supposed to be going to worship). The un-named Levite in Judges 19:1 was also from the hill country of Ephraim. Not only did he act despicably, but he incited civil war and near extermination of the Benjamites. To replenish the family of Benjamin, they plotted to kidnap women from Shiloh to be their wives (21:19). So when 1 Samuel opens, we have a few points of correlation.

The introduction to Elkanah from the hill country of Ephraim going to Shiloh takes an unexpected turn. Rather than this being a repeat of the problems at the end of Judges, this story is beginning to reverse the problems. The ultimate goal being the delivery of a King and the eventual grounding of God’s worship at the Temple in Jerusalem. Elkanah is attempting honorable worship at the proper site, as opposed to the others from the hill country of Ephraim. Samuel shall honor and respect roles rather than invent his own or disrespect God’s (like Micah and co. or like Eli and sons). This introduction to Elkanah from a literary standpoint is about transitioning the reader out of the nebulous “everybody do what they want and pretend to speak for God” into a God-given kingship and prophet.

Logistics:

So how can it be that Samuel is called an Ephraimite? I believe it more fitting to call Samuel a Levite who’s family is identified as Ephraimite, rather than call Samuel an Ephraimite who is labeled a Levite later on. Some would rather see the 1 Chronicles 6 genealogies as taking liberties in order to fit Ephraimic Samuel into the Levite line in order to invent some credentials for him and his grandson Heman. Instead, I think that 1 Samuel 1:1 is the anomaly, and that the Levite genealogies are the more dependable historical fixtures. The audience and author of 1 Samuel would have been well familiar with both Samuel and Heman’s legacies. Therefore the introduction as “an Ephraimite” would have been shocking. Therefore this is the passage that needs explained moreso than 1 Chronicles 6.

First, the identification as “an Ephraimite” in 1 Samuel 1:1 may be likened to Judges 17:7. The Levite there was from “Bethlehem in Judah, of the family of Judah, who was a Levite and he was staying there.” The Levites who were given portions from each of the tribes could have such close ties to their kinsmen that they might even identify as one of them. This Levite was “of the family of Judah” by means of living amongst them, perhaps even intermarrying with them. The Priestly family was given cities from among Judah (Joshua 21:4), therefore it is more likely that this Levite was of a priestly background (this was the assumption of Micah). Zuph, on the other hand, has integrated with the Ephraimites because Ephraim sponsored the Kohathites (Joshua 21:5).

Second, cities from Ephraim were given to the Kohathites as their inheritance (Joshua 21:5). Specifically mentioned is Shechem “in the hill country of Ephraim” (Joshua 21:21). Now, Samuel was said to be from Ramah, which is listed as a inheritance to Benjamin (Joshua 18:25). The most likely geographic placement of Ramah would be close to Gibeah, another Benjamite city where Saul was from (Joshua 18:28). But we know that the tribal allotments were not always honored (as in the case with the Danites in Judges 18). Judges 19:13-16 feels the need to point out that the Ephraimite was different from the Benjamites who owned Gibeah. The point is that the Levites appeared mobile at the end of Judges, and it should not surprise us if a Levite family from Kohath gravitates away from the original Ephraimite city allotments. Therefore if an Ephraimic Levite family gravitated to Ramah (owned by Benjamin) it would make sense to distinguish them as Ephramites in opposition to the native Benjamites. In fact, Zuph’s family became so influential that the area was known as “the land of Zuph” (1 Samuel 9:4-5, which indicates that Ramah, indeed was not in the normal Ephraimite territory, but in Benjamite regions). Indicating Zuph’s Ephramic association makes sense on a geopolitical basis.

Third, although the Priestly families were charged to keep their lines “of his own people,” (Leviticus 21:14) the rest of the Levite families were not given that restriction. If interpreted strictly, the Priests were to keep the family line within the tribe of Levi. But no such restrictions apply to the rest of the Levites, letting them remain free to intermarry with the other tribes. The responsibilities for the Levitical duties pass down through the sons. The inheritance of the land primarily passed through sons as well, although daughters could inherit land when sons are not part of the picture (Numbers 36). Dual tribal-ship was never a thing. A person was from one tribe only and had the responsibilities of that tribal family (Numbers 36:6-9). Since the Levites were taken care of through goodwill sharing of the people, a time of spiritual degradation is a time of destitution for a Levite. It would not be surprising at all that a destitute Levite family (Zuph, lets propose for a moment) intermarries with a neighboring Ephraimite family and chooses to identify as Ephraimite. This would fit Samuel’s situation from a story telling point of view. Hannah’s dedication of her firstborn was not just a firstfruits offering, but a way of correcting generations of role-abdication. Samuel would have become the first in the family in many generations to actually fulfill their true obligations as a Kohathite: caring for the tabernacle items. Correcting roles is a theme of the Samuel story (the line of Eli is another study in the same vein).

Fourth, it might be advantageous to distance Samuel from the priestly line. As mentioned before, Benjamin, Judah, and Simeon were given the priestly families to care for. Ephraim, Dan, and Mannasseh were given the Kohathites (Joshua 21). Therefore, by distinguishing Samuel as an Ephramic Levite (as I am interpreting here), the author is placing barriers to Samuel serving as priest. Didn’t Samuel act as a priest? No. He did not. Samuel’s ministry to Eli was ministry to Eli personally and the logistics of the house of God, not training to be an ordained priest. Samuel does not serve as priest in the tabernacle, nor do his sons. Samuel’s role was chosen by God to be a prophet. Samuel leaves Shiloh, and does not accompany the journey to Nob. Instead, he returns home to Ramah (“High place”) where there was a reputation of prophecy (Judges 4:5; 1 Samuel 19:18-24). The sacrifices which Samuel is in the habit of offering (1 Samuel 7:17; 9:13; 13:8-13; 16:2-3) were prophetic, like those of Noah (Genesis 8:20), Abraham (Genesis 15:9), Balaam (Numbers 23:4), and Elijah (1 Kings 18:38). Atonement or dedication sacrifices according the the regulations of the Law were strictly to be done by the priests at the tent of meeting (tabernacle) (Leviticus 17:8-9). Therefore these sacrifices were of another type. Saul’s error in 1 Samuel 13:8ff was not his lineage, but his presumption and disobedience. He was trying to take the role of a prophet without authority, and was directly overlooking something God had told him to do (presumably to wait for Samuel). Samuel takes steps to distance himself from the priesthood (and indeed, Eli’s cursed family line) by moving to a different city, engaging in different sacrifices, and (in 1 Samuel 1:1) identifying with Ephraim rather than Benjamin. By doing these things, Samuel honors his role and does not tempt the people nor his own family to fill the role of High-Priest, even though he would have done very well in that role. It’s not where God placed him. We see this theme throughout the Samuel books as Saul, David, Jonathan, and even David’s children continually grapple with retaining or rejecting their given role.

Literary Review:

Samuel’s genealogy is very consistent in all its tellings (once you weed out variances in name spellings and format). Samuel is clearly from the line of Kohath. His designation in 1 Samuel 1:1 is an anomaly which serves literary and thematic purposes. It is not a designation which intends to denote lineage, but region and role. Just as Elimelech and Jesse were called Ephrathites for living at Ephrathah (but were not descended from Ephrathah), Zuph is called Ephraimite for regional purposes. It contrasts the earlier stories of Levites and Ephraimites and their failures with Samuel’s righteousness. It distinguishes the Zuphite clan from the local Benjamites. It distinguishes the Ephramic Levites from the Benjamic Levites and marks Samuel’s role as that of a Kohathite, not an Aaronic priest.

Theological Lessons:

God’s mercy knows no limits. Even in the whole mess through the period of Judges, God still gives chances to undeserving families. No matter how you read it, Elkanah’s family did not deserve to be heard and blessed. God chooses Samuel, a child from a wandering family to be a prophet, while Eli continued to disrespect his High Priestly role. Samuel’s attention to obedience and roles becomes a type for what God wanted all along. How amazing is it that one of the descendants of Korah (the infamous rebeller from Numbers 16) would have the chance to seize the high priesthood for himself, but instead walked away from the temptation. No matter who we are or where we are from, God has given us a role and we must seek to fill it in obedience, trust, and respect. This also anticipates Jesus’ messianic coming. The messiah was from David, the son of an Ephrathite. Samuel was also a son of an Ephra*imite. Samuel was somehow both an Ephraimite and a Levite. Jesus is somehow the Son of Man and the Son of God. Samuel appears to be from a different family than we would expect for his role. Jesus was from Nazareth, and his birth in Ephrathah was not common knowledge. Samuel honored both the family role and the prophetic role God had given him. Jesus does the same, filling shoes as the son of David and Son of God. Samuel offered different sacrifices than the Temple atonement. which were in accordance with obedience (1 Samuel 15:22; Matthew 12:7). Jesus offers the better sacrifice of His own blood, in full obedience to the Father, and surpasses all forms of sacrifice before Him. Samuel was rejected by the people as leader, symbolizing the people’s rejection of God’s kingship (1 Samuel 8). Jesus was rejected as king, crowned with thorns and anointed with spit. Samuel died alone and in sorrow, weeping over the people’s rejection of God’s true king. He came back from the dead in spirit to issue a proclamation of judgment to Saul. Jesus rose from the dead in both spirit and body and becomes both judge of the wicked but also savior for those who commit themselves to obedience. We live in a place where we don’t really belong. We identify with our culture insofar as our humanity is concerned, but we must identify ourselves by the role: children of God. Only by full commitment to this role will we honor God’s plan for us and mirror the life of Jesus the Messiah.

Featured Image Credit:

John Heseltine / Pam Masco / FreeBibleimages.org